The same populist forces that brought Donald Trump to office could also enable a politician from the progressive left to succeed him. How would a president in the vein of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or Zohran Mamdani change U.S. foreign policy and the world?

Transcript

Note: this is an AI-generated transcript and may contain errors

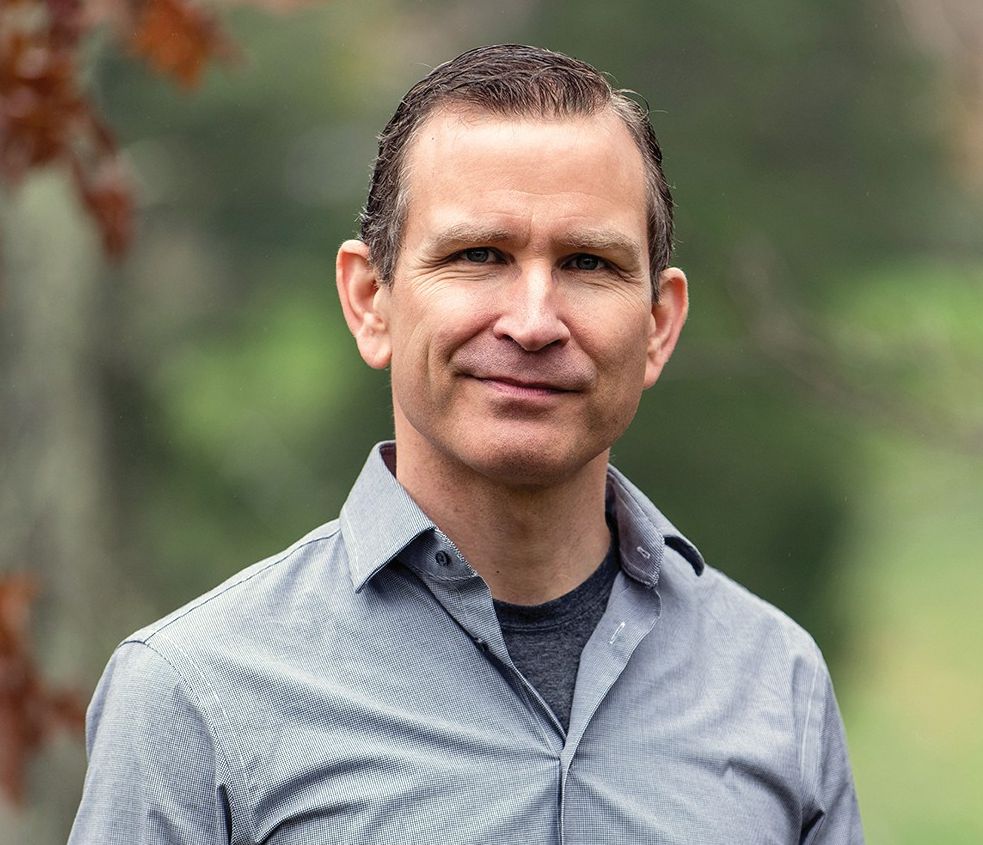

Jon Bateman: Donald Trump's foreign policy has so deeply changed the world that it's easy to forget a Democrat could be commander-in-chief in just a few short years. And that person wouldn't just put everything back the way it was before. They can't and they won't want to. So we might be in for another major global reset. Now what that actually looks like will depend on a raging factional battle between the progressive left and the moderate center left. These two camps were deeply divided over Gaza, but they also have very different worldviews. My guest today is Matt Duss, one of the most prominent foreign policy thinkers on the American left. He was Bernie Sanders' foreign policy advisor and now helps to lead a proudly progressive think tank. If someone like AOC or Ro Khanna becomes the Democratic nominee, people like Matt will have a lot of influence. So I asked him the big questions. What should we do about tariffs and alliances? What kind of military should we have? And whether it's worth fighting China to save Taiwan. I'm John Bateman, and this is The World Unpacked. Matt Duss, welcome to the World Unpacked!

Matt Duss: Thanks, Jon, glad to be here.

Jon Bateman: You are not just a thoughtful, deeply-informed, seasoned analyst of foreign affairs, but you are a- Go on. Go on! No, thank you. Well, you're also a bearded glasses-wearing millennial, which I just have huge natural affinity for.

Matt Duss: I do have to like respectfully correct you. I am a Gen Xer. Wow Do they do make that mistake because I'm much less mature

Jon Bateman: You also are a card-carrying member of a very important part of the foreign policy debate, the foreign-policy progressive community, the Foreign Policy of the Left. What is progressive foreign policy? What are its features? What are it's goals? How does it see the world?

Matt Duss: Any country's foreign policy is to promote the security and the prosperity of that country's people. I think everyone, no matter where you are on the political ideological spectrum, agree. That's the purpose of foreign policy. But as a progressive, I think the word solidarity really matters. So I think we promote a vision of America's role in the world that recognizes that our security and our prosperity is really bound up with communities around the world. While as we've learned over the past decades, our ability to export democracy, to export rights and freedom is I think a bit more limited than many of us or many, not us, but I think many past U.S. Governments have imagined. I still think we do have the ability to promote certain values and principles, but at the very least, I think we should endeavor not to export harm. I think we should make sure that when we're trying to advance our own security and prosperity that we don't export insecurity and poverty onto others. So I think that is a kind of first principle of progressive foreign policy is seeking the path of least harm.

Jon Bateman: One idea is solidarity. This, of course, is a well-known idea in the politics of the left generally, often kind of brings to mind things like labor unions or kind of international rights movements, the notion that perhaps there's kind of dispossessed groups that should be uniting together. But could I just draw you out on, when you say solidarity, who or what should the U.S. Be in solidarity with on the international stage.

Matt Duss: Yeah, I mean, I think we should be in solidarity first with other democracies, not only I think we should be in solidarity with people in undemocratic countries who are trying to achieve their own rights, their own freedom, whether it's Palestinians, who's, you know, we have been funding and supporting the occupation and dismemberment of Palestine for many decades. I think We also need to apply this to the people protesting in Iran. We've been sanctioning and in various forms of conflict with the government of Iran. We've had various rounds of protests in Iran over the past decades. One of the largest is something we just saw that now seems to have been suppressed once again with enormous violence and savagery by the Iranian government. But I don't want to pretend that it's the answer of like, okay, what do we do then is really cut and dried. I do not believe that we can achieve the activists in Iran, their democratic goals, for those of them who have democratic goals. And from what I've seen, many of them do by simply military strikes on the Iranian regime. I think it's much more complicated than that. Or another example I would also use is the example of Ukraine. Um, you know, there has been, I think a pretty vigorous debate about the, what the best policy for the U S toward Ukraine in response to the Russian invasion in February, 2022. I mean, my view has been that helping Ukraine defend itself, um, from the invasion of a larger, more powerful neighbor is, is, a progressive one. I mean there are progressive principles, um very important ones that I think that are served here. Now that doesn't mean we should just have an open-ended blank check for Ukraine while I and many other colleagues. On the progressive side has said, yeah, we need to seek a way to end this war. Unfortunately, one of those people who doesn't want to do it is Vladimir Putin. And we need, I think, grapple with that. What does that mean then? Do we simply continue supporting this war as long as the Ukrainians want? What does it really mean to get toward a durable end to this war that, again, is the path of least harm?

Jon Bateman: Okay, so if international solidarity with other democracies with people seeking their rights and fulfilling life, if that's the kind of orienting vision, what I'm also hearing is a certain amount of one might call it restraint, or a jaundiced view of what happens when the US tries to apply its power toward these or any other ends that there's a sense that US power is dangerous. It's maybe something we should have a healthy fear of overusing because of all of these unintended consequences. I use the word restraint purposefully because among foreign policy intellectuals, this is now a kind of recognized camp, the notion that US military power in particular should be much more carefully husbanded and used much more selectively. The restraint camp includes people on the left and the right. There's people in the Trump administration who identify with that point of view, although it would be hard to call President Trump himself a restrainer. Would you adopt that terminology or is there something, some daylight there between the notion of restraint and the notion a progressive foreign policy?

Matt Duss: I think the way you described it is very well done. I mean, I've worked with colleagues in their strength camp on both the left and the right, and as you just said, I mean what it is, is defined by a caution and a skepticism toward the kind of magical abilities of American military power. You know, in some cases, American power more broadly, because it's not just power that is often dangerous, it's violence. You know the use of military violence as a way to achieve our foreign policy goals, on the resort to military violence, as if it is some kind of just magic, is something we see unfortunately cropping up again and again in American foreign policy. We see it now in Trump's policy toward Venezuela, his policy toward Iran, where Trump of course is not, you're right, he's not a restrainer. I think there are clearly people inside his administration who are part of that camp, many of them who I know and have worked with. But you know, unfortunately, this is Trump seems to have adopted this kind of tendency in Washington, which is that, you know just our military is so awesome and our special forces are so awesome. Look at the way we can just roll up into Venezuela, grab their president and leave, um, look at the ways we can launch some bombers to, to devastate Iran's nuclear facilities. And it's like, well, okay, that is clearly impressive, but have you solved a problem or have you created a new set of problems? And you know we see You know, this is a kind of a, I'll call it a rot within our, our own foreign policy establishment and our broader political establishment, because, you know, Trump has learned that anytime he wants kind of around of applause, all he needs to do is blow something up. So there's any number of things that I should want a president to do to demonstrate that they are fit for the office and, and, you know, blowing stuff up does not make like the top 25, probably not even the top 100.

Jon Bateman: I think you're right that the use of military force occupies a role in U.S. Strategic and political culture. It's often seen as a mark of seriousness, of doing something, of strength, or even masculinity. In Trump's case, Trump has used it performatively and innovatively, I think, you might even say. He has launched strikes of a type that other presidents wouldn't have even contemplated. So in some ways, he's kind of fitting within this tradition. Of American use of force. In other ways, he's kind of a violence innovator and performer. So what would a progressive foreign policy say about the US military? I think there are strains within progressivism that have decades of suspicion toward what they would call militarism, military primacy. Do you have a view, and does the movement that you're a part of have a clear uniform view on should we have a military of the scope and scale that we do today? What should be its general priorities and missions within the world?

Matt Duss: I mean, I think if there's one uniform view, it's that we are spending way too much on the military. We're at a trillion dollars now. Trump just announced he wants to make it 1.5 trillion. That is crazy. When you consider all the things that Americans are denied, and we're talking about healthcare, education, the things that even when people have access to them are just incredibly expensive, especially compared to other modern developed countries. The basic social safety net that other countries take for granted. Saying that we should cut the military budget, I think, is just a simple start. The question becomes more complicated when you say, okay, what strategic choices should we make to enable these cuts? And I think there are some differences of opinion amongst progressives. How much of a kind of global footprint should the U.S. Military retain? What bases should be closed? What should stay? You know, my own view, and I think a lot of progressives recognize that You know, even though having US forces stationed all around the world does prove to be a big temptation to just use the military tool when other options are unavailable, especially when you've not resourced them as well in terms of diplomacy and other forms of aid that could have prevented you getting to the conflict point. There's also some examples of US military presence that creates less risky behavior on the part of both adversaries and allies, and that does deter conflict. Um, so as, as strange as that might be to say, I think you can point to some examples where keeping the U S military in place is the path of least harm. Um, but I do think we need to think, you know, there's kind of an assumption in Washington that if you remove the U.S. Anywhere, then everything just collapses. I think this was really part of the Biden administration's approach is that the U s you know stands as is kind of this Atlas, um, holding up the Order And if the United States withdraw or kind of downgraded its involvement Or you know, let alone god forbid You not get engaged militarily that that the whole system would collapse and it's like I kind of just motion Yeah, the whole world and say well things are collapsing and a lot of things have collapsed precisely because The United States made some wrong choices to intervene

Jon Bateman: So I grant that there's gonna be a difference of views within the kind of mini-tent of progressive foreign policy on kind of which missions do you hold on to, which missions you retain. I'd love to just get the Matt Duss view of, and I'll just push you on like, what's one thing that we should absolutely draw down on? What's one that we absolutely retain? You just get a flavor of what does it look like to have a smaller military? And what then becomes of the U.S. Role in the world and what happens in those regions.

Matt Duss: Yeah, I mean, just for one, I think we should close our military bases in the Middle East. Okay. And we've got a huge military base in Qatar, I've been there as have many other foreign policy officials. I mean I think the partnership we've developed with Qatar has, you know, actually provided some goods. I mean Qatar has proven a real interest in being a kind of conflict resolution broker, which I think is a very interesting role for them to play. It's frankly a less destructive and disruptive role. That has been played by some of our other Middle East allies like the Emirates and Israel, just to name two. But still, I don't think that having this massive military facility there is necessary to sustain that relationship. Obviously, they see it as a source of security and as a kind of sign of our commitment to the relationship. But I think there are other ways to signal the durability of that relationship that remove this temptation and this threat that this base represents to a lot of countries around the world. And I think this is rooted in this idea that the United States, you mentioned the word the restrainers. I think what restrainors have a critique of is American primacy. And I these are kind of two poles of the debate right now. You've got left-right restrainers. And then you've got left, right primacists who believe that the United States can and must maintain this massive, uh, global role that does whatever it can to prevent the rise of any near competitor. Um, and, and again, you saw this, you know, this all the Biden administration, um, take this approach. You see the Trump administration essentially take this approach, although with some very interesting differences. He sees, you know, the world as as a kind of global mafia operation with the United States being the biggest and most powerful mafia family and therefore we deserve tribute from other countries.

Jon Bateman: The primacy question, it seems like somehow the crux of a lot of what we're talking about. Oftentimes in Washington, D.C., it seems like the real debate is just about kind of where we should have primacy the most, rather than whether primacy should be a goal in and of itself, right? Yeah. So someone like Bridge Colby, you know, the undersecretary of defense for policy, he's kind of a well-known Republican, defense intellectual, and you know. So he's identified as a restrainer, but my understanding of his argument is we need in the Asia-Pacific. To deter China from taking Taiwan and to protect our interests there. Therefore, he looks at the math and the budgets and says, okay, I'm willing to give up Europe, the Middle East, whatever, kind of deleverage from some of these other areas. So that's one way to looking at it is like, we're trading primacies rather than kind of abandoning primacy. But-

Matt Duss: been called a prioritizer. Okay. And I think perfect description. So there is kind of a Venn diagram with three circles, you know, the primus is the prioritizers and the restrainers and you know sometimes prioritizes and restrain. There are things that that we agree on because they're like, yeah, we're wasting time in the Middle East. We're getting drawn in to kind of, you know on behalf of these client states to solve their problems for them often with And this is bad for us in a lot of ways, but He, as you said, I think you described his approach correctly. He just believes we're wasting time in some of these other regions and we really need to focus attention and resources on China and Asia.

Jon Bateman: So does the progressive view go one step further and say we reject primacy? And what would that look like?

Matt Duss: No, I think we do, at least primacy as it's been defined over the past, you know, in the post-war era, which is that the United States is this unchallenged global military hegemon. That you know we're the world's policeman, that we get to determine what the rules of the rules-based order are, and we almost always define them in ways that benefit us and our friends and are used as a cudgel against our adversaries and people who aren't our friends. Um, which is part of what has, I think, undermined the entire premise of the rules-based order, um, which we saw, I think most graphically in, in Gaza, where, you know, you know, when you compare Ukraine to Gaza, um the fact that this, this, this double standard was so egregiously, um applied, um by this president, Joe Biden, who was seen by Washington as kind of the embodiment of the Washington, the wise Washington foreign policy person, um I think for, for him and his team. Of experts to be the ones to cock this up so badly, I think is, you know, underlined this I think a lot more than if it was someone like Donald Trump who everyone understands he's a hypocritical and doesn't really even pretend to apply any real principle or value to this. But I do think even, you now, as I define it, and again I think there's an abate among progressives about how much the United States needs to assert and uphold its own influence and power. In ways other than military. My own view is that the United States, by virtue of our huge economy, our network of relationships and alliances, the role that we've played historically as a kind of global convener to address shared challenges, the U.S. Does have, in my view, a major role to play on just issues of medicine and food and shelter, humanitarian aid. And in yes upholding I think a sense of universal rights I mean this is something that's in our declaration of independence we'll celebrate 250 years of that document this summer

Jon Bateman: You've brought up some of the other tools or offerings that America has to exert power and influence beyond the military, right? Humanitarian aid, our soft power, our example, our diplomacy, cooperation in international institutions multilaterally. Now, those tools can also be wielded coercively, right? Just as Trump is a violence innovator, he also is innovating in these other areas. He has turned access to U.S. Markets into a kind of international weapon through the supercharging of tariffs. Biden. Began to innovate in the area of export controls, which is now also being greatly enhanced through Trump's efforts. If we kind of set the military or militarism to the side and start to think about these other tools, what's your view of these? Is it just of a piece with the military tool because it's all kind of coercive and potentially oppressive, dangerous, or? Maybe if we set aside the military tools, we might actually want to resort to the other tools more instead.

Matt Duss: I'm not someone who opposes tariffs. I think for the longest time we had this kind of economic theology, um, that was like, no, tariffs are just bad. Never use them with just free trade is this ultimate good. And we must just, there must, nothing should stand in the way of free trade. Um, and I think it took far too long for the U S you know, for the U S government to come around to this idea that this was a false ideology. I think there was a really important speech that national security advisor, Jake Sullivan gave. In, uh, I think it was, um, may or spring, spring of 2023. I remember going, I was at, I was at Carnegie at the time. He gave it two doors down at, or right next door at the Brookings institution where it's kind of a landmark speech about, you know, the old economic theory really didn't pan out and we need a new new approach to global economics. The government, you know, the U S government needs to be in the business of helping plan the economy. The government has a role to play. In managing trade in a way that would have been seen as heresy 20 years. The way Trump has used tariffs is just as a form of another sanction, you know, it's not a way to kind of address trade imbalances. It's just, you see the way he uses is like, Oh, you did something I don't like. I can't, you know, he spits out a percentage. This is how much we're going to tariff you. I mean, it really, there's no, you know, you there's no rhyme or reason to it other than this is just something I can use to bash you until you decide to say sorry or decide to give me some present and then I'll lower the tariff. I'll remove the tarif, but it's just, it's just another form of Having said that, we also need to look at these, you know, so-called nonviolent tools of sanction that the U.S. Has been using even before 9-11, but especially since the attacks of September 11th, 2001. I think it's safe to say that that power has been massively abused. Certainly, I see it is a non-military tool that in certain cases I think is fine to use, especially if you're focusing on individuals. You know the the Magnitsky sanctions. I think are really important tool that focuses on specific human rights abusers, denies them access to banks, to travel, and things like that. But we've seen sanctions imposed, like huge sexual sanctions imposed on countries like Iran, like Venezuela, that have just utterly crashed their economy, that has created an enormous misery. It's hard to point to very many examples where these kinds of sanctions have produced a better outcome. Now you can point to in the case of Iran, the Iran nuclear agreement, the JCPOA. A sanctions, as I see it, are only really effective if you've said, listen, we don't like this thing that you're doing, we're gonna change this behavior and once you change this behavioral, the sanction will be lifted.

Jon Bateman: Yeah, I grant you that these kind of easy buttons of like a precision military strike that's demonstrative or sanctions or in Trump's case a tariff, once the tool exists, there's little that can be done about it on the other side often because of American might. It creates a temptation and a mission creep and it becomes normalized. On the other hand, if the progressive view is kind of... Suspicion of the misuse of these tools. So, you know, we kind of want to take more of the military tools off the table. Maybe you also want to take more of the sanctions off the tables, take maybe more of the tariffs or export controls off the the table? Are you walking into a world where a president doesn't have a lot of tools left? And maybe that's okay if one is more afraid of what a president might do than wanting to vest that person. With the power to achieve national interests and steer the world. But what's the limiting principle where a progressive president in the future just wouldn't have enough power or influence or options? How do you ensure that doesn't happen?

Matt Duss: Even if being more cautious about the use of the military compared to how we've used it in the recent past. Even if being cautious and skeptical about the financial sanctions compared to we've use these tools in the very recent past, even dialing it down a bit is still a lot of power. We've got a ways to go, I agree. I kind of joke, American power, the way it's been used over the past several decades, It's like listening to like death metal at top volume. And when you've been listening to Slayer that long, listening to Zeppelin sounds like just smooth jazz. Zeppelins feel pretty hard rock. So I don't know, maybe we should try playing Zeppeline for a little while. It's still pretty, there's still a lot of tools a president can use that can make a difference. It's just not always dialing it up to 11 all the time. In terms of the power of progressive presidents use, I think, first of all, grounding it in popular support. One kind of data point that I've brought up a lot is in every election since the end of the Cold War, since the 1992 election. With the one exception of 2004, the Kerry-Bush election of 2004. The less militaristic president has won. The more pro-peace president has won. Now, I'm not going to say that that is the reason they won, but I do think we have an interesting data set at this point. How would you classify Trump out of curiosity? I would say that Trump in 2016, when he won, and again in 2024, when won, got to the Democrats' left on foreign policy. He, he, he was less militaristic than Hillary Clinton. He was less militarily. He really leaned into a pro-peace message in the last weeks of the 2024 election. I think the opposite was true in 2020. Biden was the one claiming I want to end the forever wars. I really want to get out of Afghanistan. I'm going to down, I'm gonna down, you know, I'll I'm going to do, I going to get back into the Iran nuclear deal. Now he didn't, he didn't keep a lot of those promises, unfortunately, but that is the way he campaigned. Now, of course, a lot of these presidents, once they get into office, of course, they sit in that chair, they look at this massive military and they're like, okay, what can I do with it? Um, but I do think it's important to note they campaign, um, on much more of a pro-peace platform. It does, it does suggest to me that there is a real appetite for this among a constituency of American voters, and I would really love to see a progressive president really mobilize that. In a real way, and if there's any upside to Trump's presidency, and I think they are very few, he has shown that a president has a lot of space to run on foreign policy and a whole range of other issues. Trump's election first in 2016, the phenomenon of the Trump candidacy, the way he just took over the Republican field, was as a critique of the system. Yeah, and obviously Bernie Sanders was a part of this too

Jon Bateman: The anti-system energy that Trump represents is available to a variety of politicians should they choose to ride it, right? And there is a left version of this. Bernie Sanders represents that, AOC represents that. You know, I think one place where rubber meets the road in terms of the electoral politics of foreign policy is Gaza. I don't know what to make of these arguments, but undoubtedly, the progressives, in addition to making a moral case and a strategic case for being much tougher on Netanyahu and exerting tangible U.S. Pressure in order to shift the course of Israel's war in Gaza post-October 7th, There also has been a political electoral argument made, that the unwillingness of Biden and Kamala Harris to follow that course deflated enthusiasm amongst Arab voters in Michigan, left-leaning voters, even independent and right-leaning voters in some cases. I don't know what to make of this argument, but what do you make of it?

Matt Duss: It's hard to say that this is why Harris lost. I think there was a lot of evidence that it, as you said, it really depressed enthusiasm. I think it really depressed, you know, get out the vote efforts on the part in a lot of states and a lot, a lot areas. People who would have been inclined to at least show up and do the phone banking and do the door knocking. We're really turned off by this certainly we've seen not just the Arab American community But also young voters young Democrats were just outraged by it But I think there's a there's an extent to which the Gaza issue Stands in for a broader kind of foreign policy debate. It really is about how should America act in the world But more than that for people who don't really care about foreign policy Perhaps don't care about Israel and Palestine or Gaza all that much. Although I don't think we can we can't dismiss the fact that everyone, they could see these images on their phone, they could them on the news. And they knew that what they were hearing from Joe Biden, they knew what they're hearing from Kamala Harris was not reflecting reality. And they felt like they were being lied to. They were being gaslit. Um, and that really diminished trust and that fed the idea that, you know, these people are just not for real. Um, And even if they're making a lot of promises, the fact that they feel the need to kind of just repeat these unconvincing talking points really does not give a lot confidence that they're going to fight for me for these other good things they're promising. Now I point to an example of someone where that worked in the other direction and that's Zohran Mamdani. In New York. Because I'm going to stand firm on opposition to this war. I'm gonna stand firm on my opposition to the Biden administration's policy and US policy. And I think that impressed a lot of people because even if they disagreed with him in that, even if they don't really care about the issue at all, it was he signaled the listen, I am for real. Yeah. You know, you can believe me when I talk about all these other things. Because I've been challenged by this entire, you know, institutional status quo, this machinery. Of propaganda through everything it had at me.

Jon Bateman: I stood firm. Just one more point about Gaza, because on one level, it's not surprising that this emerged as the cleavage between progressives and maybe kind of the centrist blob in the Democratic Party, right? It's so morally painful, and it forces a clear separation between some of the kind strategic compromises that people make for political and global reasons. And just that the idealism that motivates progressivism. So I get that. On another level though, most commentators, and it sounds like maybe you're also one of these people, view the Middle East generally as of declining importance to the US and that the most important debates that we maybe should be having are about China, for example, or Asia generally, our relationship with Europe, you know, and so on, the kind of the big rocks. But really, I think China. Um, is there a missing progressive China policy, you know, or should we be having more debates about that.

Matt Duss: I mean, I think we are having some debates about China among the progressive left. I think, you know, the people like you mentioned, my colleague, Van Jackson, he's written a lot about this. He and my other colleague, Mike Brennis wrote a fantastic book that was released just last year called The Rival Reparal Against Strategic Competition, making out the progressive case for why US-China competition as the focusing. Kind of lens of all American foreign policy is bad for our foreign policy and also bad for our democracy. I think you've got Jake Werner over at the Quincy Institute, you know, a kind of restraint organization that kind of takes a trans-partisan approach, but I do think Jake is a really good progressive voice on these issues.

Jon Bateman: And maybe I'm being too unfair there because I wasn't accounting for all the important intellectual work that you and people of our kind of class perform. But I'll just say, for example, I'm sure AOC has a position on China. It doesn't seem to be central to her public persona. Same thing of mom, Donnie, Bernie, am I wrong about that?

Matt Duss: Well, yes, you're right. She does have a position. Bernie has a position he wrote a piece about China specifically back at the beginning of the, of the Biden presidency. Um, you know, in, in the great religious doc, the great religious journal of American foreign policy, foreign affairs. But I also think, and this is where, I don't wanna, I think progressives definitely have the ones I mentioned and others, people like Ro Khanna, people like Ilhan Omar, Pramila Jayapal, I could run down a list of people who really have spoken out on a whole range of foreign policy issues, but I do think progressivists and the populist left, whatever term you wanna use, has had a really sound theory of the case on this for a while, not just since 2016, but like my own entry into politics, into political activism was in the late 90s in the alter globalization movement, you know, protesting these, the World Bank, IMF, ETO, and that movement I think had a really, really pretty good theory of what was wrong is that, you know, global free trade, this religion of neoliberalism and, you know lowering taxes and lowering barriers to entry and lowering worker protections was going to make everyone richer. It didn't. It made the world more corrupt. It made made countries less equal. Um, and it led directly, you know, a lot of other things happened between, between, you now and then, um, but basically as someone who was in that room, when, when Jake Sullivan gave the speech, I mentioned it was remarkable for me to be sitting there thinking, you know, 22 years ago, I was, you know, occupying a, a, an intersection, you know, 10 blocks away at the world bank. Um, now I'm hearing the national security advisor. You'll basically admit that, yeah, you protesters were kind of right about a lot of these things. Now it's way too long for that realization to come, but it's here now and I do think you had people like Bernie and others who were pointing this out at the time.

Jon Bateman: It's a fascinating example of Jake's speech because progressives often see themselves as kind of on the outside of institutions looking in and sort of bemoaning their anti-system status and the fact that kind of mainstream power structures are sort of suppressing them. And yet in another way, they can sometimes win a longer and subtler battle of ideas and kind of win by losing in a sense. I think you're right that

Matt Duss: I'd rather win by winning, but you know, yeah.

Jon Bateman: Well, OK, so let's say you win by winning, right? President AOC, you know, maybe we could just close on the toughest issue that she might face in her presidency in terms of foreign policy, which is a potential confrontation with China. I keep coming back to this because she might come into office in 2028, 2032, 2036 and say, you know, my agenda. Is the following. I want to deleverage from the Middle East. I want express solidarity with democratic alliances. But as we know of every president, events intervene and she might have to be facing this awful decision of do we defend Taiwan in a crisis? Do we apply these lethal sanctions and tariffs to China in that crisis? The tools of American power that progressives rightly have serious questions about. You're the national security advisor. I have no doubt, Matt, that you could aspire to that role under a president AOC. What would you tell her?

Matt Duss: Well, again, not going to speak for her, um, just my own view, my own kind of advice here would be like, let's not get to that point, what are steps you can take now, uh, to, to maintain, you know, yes, and often unsatisfying status quo, but is frankly, I think the best of some bad options, which are often what you're faced with in foreign policy. Um, you, know, a lot of these hypotheticals and I don't blame you for bringing it up, it's an important one to talk about. Often assume, okay, we've gotten to the point where like, there is this war. It's like, okay. We are not there yet. What can we do between, you know, starting now to make sure we don't get there? Um, and I think in the case of Taiwan, it's, you know, I think there, again, there's a status quo where the United States does, does not support, um, um any, any side taking unilateral action. And we had some interesting conversations, especially with, you know progressive activists. In Taiwan who are very pro-independence, but yet who still understood that there's really no path to independence right now. There's really no realistic path given the massive power China has, given how China tends to respond when these issues come up. And their approach is, you know, let's just maintain this situation as best we can. And as I said, possibly a better opportunities present themselves in the future. But in the meantime, let us do what we can to secure and defend and strengthens in. Taiwan's internal democracy, and I think that's a good place for us to start.

Jon Bateman: Matt, you've been very game to face relentless hypotheticals and queries from me. I just wanna say, I think we have to have you back on this show because this conversation is a down payment on a set of very serious and critical debates that the Democratic Party and its coalition will need to have. And so people like you are helping our audience and others understand what the presidential debates will be. In a year or two years that haven't happened yet, and that need to happen, just like they'll be happening in the GOP as well. Thank you so much for your time and expertise, Matt. I really appreciate it.

Matt Duss: No, I really appreciate it. Really appreciated the conversation and really love what you're doing here. So thanks a lot.